| Alan Garrow Didache |

the problem page

|

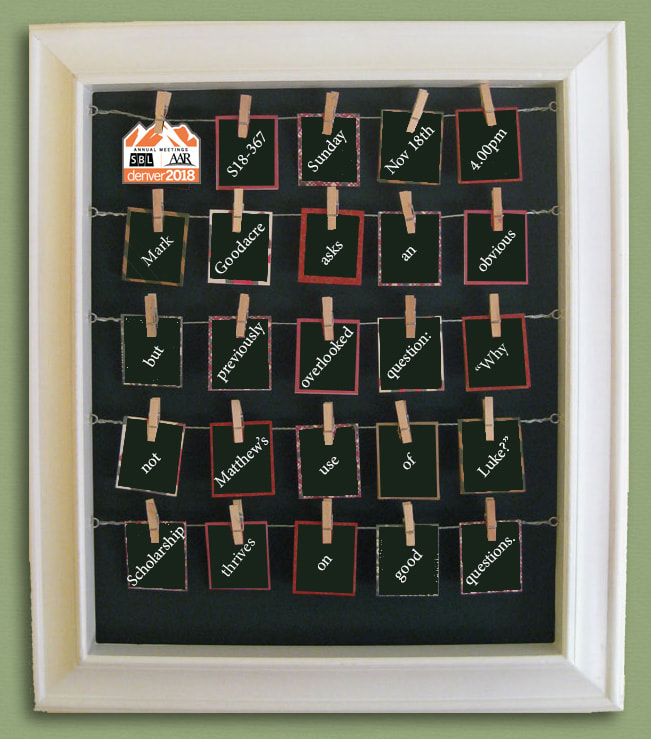

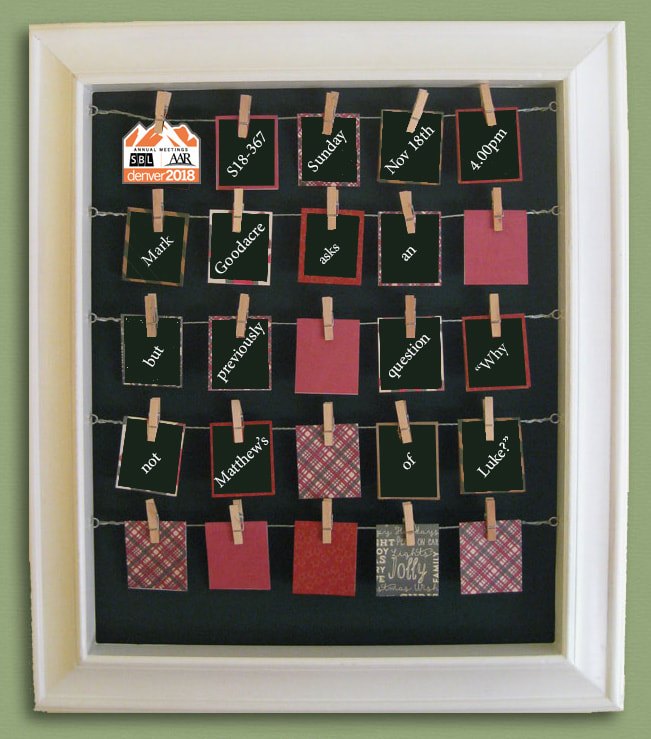

I’d like to use this final Calendar entry to express my admiration and gratitude for Mark Goodacre. Mark may not take this as much of a compliment, but he is my kind of scholar. I admire his willingness to challenge the prevailing consensus, I enjoy the ease and clarity of his written prose, and I very much appreciate his willingness to present 'live' rather than reciting a full script. The aspect of his scholarship for which I am most grateful, however, is his willingness to engage. By engaging with the $1,000 Challenge, being willing to respond to my paper at BNTC 2018, and then presenting the paper, ‘Why not Matthew’s use of Luke?’ at SBL Denver 2018, Mark has done more than anyone to alert the wider scholarly community to the fact that an alternative solution to the Synoptic Problem is a topic of current scholarly debate. And, now that scholarly attention is focussed in this direction, Mark Goodacre’s SBL paper offers an important opportunity to learn whether this route is worthy of further attention and exploration. Mark Goodacre’s paper ‘Why not Matthew’s use of Luke?’ presents such an opportunity because of the calibre of its presenter. Mark has spent the majority of his distinguished scholarly career promoting and defending the Farrer Hypothesis. This means he is superbly equipped to find the worst flaw in the case for Matthew's use of Luke – as well as being highly motivated to do so. In short, if Mark Goodacre cannot find the flaw in the case for Matthew’s use of Luke, then it is doubtful that anyone can. With this in mind it is worth noticing what is missing from the abstract for his SBL paper: Why Not Matthew's Use of Luke? It may be that, in the months between writing this abstract and actually delivering the paper, Mark Goodacre will have identified some more substantial reason for rejecting the case for Matthew’s use of Luke. Taking the abstract as it stands, however, note what is missing:

First, there is no suggestion that Mt3rd requires multiple, improbable levels of coincidence – the weakness that most seriously undermines the 2DH. Second, there is no suggestion that Mt3rd requires Matthew to treat one of his sources in a way that is unique in the period, mechanically/physically exceptionally demanding, and out of tune with the way Matthew treats his other sources – the type of weakness that most seriously undermines the FH. What remains instead are four phenomena that are all open to more than one interpretation; they are all capable of being explained if Matthew used Luke. If this is how things continue to stand after SBL session S18-347 (Sunday 18th November, at 4.00pm in Room 302 (Street Level) – Convention Centre (CC)), then a new era of enquiry will have been thrown wide open. And if that does indeed happen, then anyone seeking a solution to the Synoptic Problem more satisfying than those repeatedly discussed to date, will have yet another reason to thank Mark Goodacre. ------- If you've not seen all the previous entries in the Calendar, I recommend some particular highlights: Day 4: Richard Bauckham answers the question: How did you come to think that Matthew probably used Luke? Day 11: Ron Huggins tells the story behind his article 'Matthean Posteriority: a preliminary proposal', NovT (1992) Day 21: Tim Murray offers his reaction to the Garrow/Goodacre debate at BNTC 2018.

0 Comments

Supporters of the Two Document Hypothesis do not claim that their hypothesis is flawless: "[E]ven though I have (unashamedly?!) sought in this paper to argue that the weaknesses of the 2DH are possibly less than those of other competing hypotheses today, I hope that I have shown that this theory too is open to questioning. It would be a brave, even foolhardy, person who claimed absolute certainty for the correctness of his/her viewpoint." “No hypothesis is without its difficulties, and for any of the existing Synoptic hypotheses there are sets of data which the hypothesis does not explain very well” When pressed to be more specific, 2DH supporters generally point to the problem of the Minor Agreements – places where Matthew and Luke agree against Mark. For example, Gerald Downing, in ‘Plausibility, Probability, and the Synoptic Hypotheses’ ETL (2017) 313-337, devotes considerable attention to attempting to explain the most famous of all the Minor Agreements: Matthew and Luke have: ‘Prophesy … who is it that struck you?’, whereas Mark has only ‘Prophesy!’ (Mark 14.65//Luke 22.65//Matt 26.68).

In my view, however, the Minor Agreements – though certainly problematic for the 2DH – are not its worst weakness. A much more severe problem is posed by those passages where Matthew and Luke agree almost exactly (and where there is no direct parallel in Mark). The problem, in a nutshell, is that ancient writers tended not to copy their sources verbatim. Matthew’s treatment of Mark is unusual in this regard inasmuch as Matthew sometimes copies Mark with a high degree of verbatim faithfulness. Luke’s treatment of Mark is, however, more conventional – he tends to paraphrase, rather than copy Mark word for word. We can see in some detail what happens when one author paraphrases his sources while another is more faithful, by looking at the extent to which Matthew and Luke exactly agree in their treatment of Mark. The answer is that they never come close to both copying Mark in exactly the same way for a whole paragraph. The closest they come is in The Parable of the Fig Tree (Matt 24.32-36//Mark 13.28.32//Luke 21.29.33) where 37% of the 86 words fall within Strings of Verbatim Agreement of 4 words or more. The next closest example is, ‘If any man would come after me …’ (Matt 16.24-28//Mark 8.34-9.1//Luke 9.23-27), where 29% of the 110 words fall within strings of verbatim agreement of 4 words or more. Beyond this there is no other example where more than 20% of a given paragraph falls within Strings of Verbatim Agreement of 4 words or more that are identical in Matthew, Mark and Luke. Contrast this with the numerous occasions where 96-50% of the words shared by Matthew and Luke fall within Strings of Verbatim Agreement of 4 words or more (e.g. Matt 6.24//Luke 6.13; Matt 3.12//Luke 3.17; Matt 23.37-39//Luke 13.34-35; Matt 3.7-10//Luke 3.7-9; Matt 12.43-45//Lujke 11.24-26; Matt 11.25-27//Luke 10.21-22; Matt 24.45-51//Luke 12.41-46; Matt 6.22-23//Luke 11.34-36; Matt 7.7-11//Luke 11.9-13; Matt 13.33//Luke 13.20-21, and others). What the 2DH requires, therefore, is that Luke had a particular desire to copy Q exceptionally closely – significantly more closely than he copied Mark. Moreover, this desire has to be mirrored by Matthew – who is required to have had the same attitude to the same passages. Moreover, Matthew and Luke are required coincidentally to have had access to virtually identical copies of Q – even though they were writing in times and places that prevented them from having any direct knowledge one of the other. Q is generally understood to be significantly more ancient than Matthew and Luke and is sometimes attributed to village scribes in rural Galilee. If this were indeed the case, it is necessary to suppose that Matthew and Luke both inherited versions of Q that had been virtually identically adapted (or left pristine) over the decades. Furthermore, it is necessary to suppose that Matthew and Luke both thought that the text of Q they had inherited was, for significant passages, incapable of further improvement (or they both happened to improve it in virtually identical ways). When, in addition, you notice that very high levels of verbatim agreement sometimes occur in the so-called Mark-Q overlap passages (e.g. The Beelzebul Controversy, Matt 12.22-30//Luke 11.14-23), then the credibility of the 2DH is stretched still further. That is to say, even though at least two distinctly different versions of such events were in circulation (as evidenced by Mark 3.22-27 and perhaps also by Matt 9.32-34; John 10.19-21 and Thomas 35) the copies of Q that came down to Luke and Matthew were both equally unaffected (or equally affected) by that environment of diversity. If there were some really cast iron reason why Luke could not have used Matthew and Matthew could not have used Luke, then, of course, we would no choice but to accept these exceptional levels of coincidence (and the many further examples set out by, for example, Francis Watson in Gospel Writing(Eerdmans, 2013) 117-55). The difficulty is, however, that no-one has yet shown that Matthew could not have used Luke. (NB. As demonstrated in the full Matthew Conflator Hypothesis presentation, the standard arguments against Luke’s use of Matthew do not work in reverse). This means that we are not required to imagine (as supporters of the 2DH must), that Matthew and Luke both happened to inherit virtually identical versions of Q and happened to treat them virtually identically. Instead we can propose that passages where Matthew and Luke agree almost exactly are simply the product of Matthew copying Luke much as he also copied Mark. For texts and charts relevant to this discussion, see Video 2. Back in 1996 Mark Goodacre was prepared to allow that the Farrer Hypothesis, as defended by Michael Goulder, includes weaknesses as well as strengths: Goulder makes ... numerous criticisms of traditional approaches which his opponents will ignore at their peril and, further, his thesis has many strong points. One virtue is the simplicity of his solution to the Synoptic Problem. Another is the explanatory power of his thesis: frequently Goulder sheds new light on famous difficulties. Mark Goodacre's observation that Goulder's theory, 'demands a degree of complexity in the application which partly undermines its credibility' has been very frequently echoed in subsequent scholarship - albeit more forcefully and with greater attention to the realities of ancient compositional practices. Luke, under the Farrer Hypothesis is required to perform an extraordinarily complex set of operations on Matthew, while treating Mark in a very much more traditional and straightforward manner. All this might be forgivable if it were clearly the only way to avoid the serious problems encountered by the Two Document Hypothesis - but it is not. The difficulties faced by the Two Document Hypothesis and the difficulties faced by the Farrer Hypothesis are both resolved if we allow ourselves to contemplate a relatively simple alternative: Matthew used Luke.

Tim writes: "Like a few others, I abandoned my chosen stream at BNTC for this particular session as I was intrigued to see what Mark Goodacre had to say about Alan Garrow’s MCH. Having always been quite sceptical about Q (and even more so reading scholarship that was attempting to identify levels of redaction on Q and then speculate quite fancifully about the issues facing ‘Q communities’ at various stages of their existence…), I read Goodacre’s Case Against Q as a MRes student and that, for me, put the nail in Q’s coffin. I did not give much thought to whether Matthew used Luke or Luke Matthew and was happy to accept Goodacre’s version of the FH (although the awareness that Hengel argued for the reverse has always made me think at some point I should get around to looking into this!).

My doctoral studies did not really address the Synoptics so I pursued the issue no further, however towards the end of my PhD I was made aware that Garrow’s thesis was attracting the support of some serious scholars. Without making the effort to watch the videos or read any of Garrow’s work I turned up to the debate expecting Goodacre to offer some substantial critique against the MCH, especially given his role in the $1000 challenge. From that context, here were my reflections:

Like I say, these are the reflections of a non-synoptic scholar, but I think I understood the thrust of the arguments. To my mind it certainly established that Garrow’s thesis could not be easily dismissed (otherwise Goodacre would surely have done that, but he wasn’t able to). I look forward to further debates." The BNTC 2018 session caused Tim to review his assumptions. A similar shaking up of assumptions features at the start of the stories told by Ron Huggins, Rob MacEwen, Erik Aurelius, Richard Bauckham, and myself. Who knows, perhaps Mark Goodacre's session at SBL will encourage others to embark on a similar journey. The past few posts have focused on the question of the greatest weaknesses in the case for Matthew’s use of Luke – a subject relevant to Mark Goodacre’s paper at SBL this Sunday - 18th November, 2018. The reason for this focus on weaknesses is that the Synoptic Problem will come closest to being solved by the hypothesis that has the most minor, or most easily resolved, ‘greatest weakness’. In today’s post I will consider potential candidates in the case for Matthew’s use of Luke (and Mark). On Day 1, I notionally put a question to Bart Ehrman: What do you think is the best reason to reject the notion that Matthew used Luke? I asked this because, in the course of the $1,000 Challenge, Bart expressed his complete confidence that my ideas ‘simply don’t work’. What has emerged in my ongoing conversation with Mark Goodacre (at BNTC 2018), however, is that the point Goodacre made in the course of the $1,000 Challenge had no bearing on the question of whether Matthew used Luke – despite this being clearly identified as the point at issue. Nevertheless, Bart was evidently completely convinced by something. Unfortunately, I haven’t, as yet, had any luck finding out what that something was. Any help on this point gratefully received. Paul Foster in, “Is It Possible to Dispense with Q,” Novum Testamentum 45.4 (2003) 336, might be taken as suggesting that the greatest weakness of the Matthean Posteriority Hypothesis is its inability to account for incidents of Alternating Primitivity. As I have sought to demonstrate elsewhere, however (see Video 1), Alternating Primitivity, if it does indeed occur, has no bearing whatsoever on the question of whether Matthew used Luke directly. This phenomenon is only relevant to the separate question of whether Matthew and Luke might also have made use of shared sources. F Gerald Downing in, “Plausibility, Probability, and Synoptic Hypotheses” ETL 93.2 (2017) 313-337, identifies what he sees as a really critical weakness in the case for Mt3rd. It is absurd to imagine, he proposes, that a Matthew who knew of both Luke and Mark would fail precisely to copy both his sources wherever those sources agree exactly (in their rendering of strings of thirty-plus letters in sequence). It might equally be said, however, that it is absurd to imagine that Matthew would painstakingly work through Mark and Luke to identify such exactly agreeing material, no matter how incidental. Such an exercise would not only be exceptionally laborious – both when it comes to locating such passages and also when it comes to inserting such passages in Matthew’s wider narrative – but also it would run counter to an important Matthean agenda: to draw together similar-but-different teachings of Jesus (as found in various sources) into a single, carefully organised, more generally comprehensive, whole. More on this subject may be found in Days 14-17 of the Calendar. The majority of the direct and indirect contributors to this thread have settled, in one way or another, on one particular aspect of Mt3rd as likely to be its greatest weakness: the problem of omissions. That is to say, if Matthew knew Luke, why did he not make more substantial use of what Luke had to offer? This question is expressed in various ways by Verheyden (in quotation), Huggins, MacEwen and Garrow. It is an issue that also makes an appearance in the abstract for Goodacre’s SBL paper: “Matthew fails to include congenial Lucan details on politics, personnel, and geographical context.” It is true that, if it were possible to find an element of Luke’s text that Matthew would have been all but bound to include, then this would represent a serious problem. If, however, it is possible that Matthew had reasons to omit this material for the sake of economy, theology or practicality, then the problem is a good deal less marked. In addition, what may be said with some confidence is that the mechanics involved are straightforward. Of all the techniques in the author/copyist’s toolkit, the simplest is 'omit'. On Sunday 18th November at 4pm (Session S18-347), Mark Goodacre will provide a fuller explanation of what he sees as the most significant weaknesses in the case for Matthew’s use of Luke. If you’re at SBL/AAR Denver 2018, why not assess for yourself whether there is real substance to the problems he raises?

Ron writes: "When it comes to the question of the biggest weakness in the case for Matthew's use of Luke I have to admit I have been somewhat disappointed over the years at how little feedback I have gotten as to potential weaknesses in my theory from two-source defenders. When Edinburgh’s Paul Foster addressed Matthean Posteriority in an article he wrote back in 2003, an article in which he explored the question of whether Q can be dispensed with, the primary objection urged against my view was that ‘[t]he issue of primitivity still creates the difficulty that the most primitive version of double tradition material is not the exclusive possession of either Matthew or Luke, but seems to alternate between the two gospels.’[1] He then includes a footnote indicating that this is ‘acknowledged by Huggins.’[2] But to say that I ‘acknowledged’ this was not right. In fact I didn’t, I only said that it would be a problem if it were the case.

Then when Leuven’s Joseph Verheyden wrote a paper against Matthean Posteriority to be read at the 2010 Atlanta SBL, he mainly targeted the arguments of other defenders of the view, who approach it from differing directions from the one I take. He really only faults me once in the paper, in a passage which, to the best of my recollection, he did not actually read in the presentation itself: ‘And if Luke was granted only a marginal role as a source, why would Matthew have cared for looking it through to make some emendations to Mark’s text here and there? It is true, of course, that there is no rule on how much an author should take over from his source, but it is certainly not a rule either that, as Huggins argues, “the very extent of the material Luke has in addition to Mark rules against assuming that Matthew would have tried to include both to the same extent.” One would rather expect the opposite to be the case: provided with this amount of extra material, why could Matthew not have indulged in it without setting any limits for himself?’[3] But in my own mind my argument there still satisfies there. The limits Matthew set upon himself were in no way arbitrary. In defense of this I would point, for example, to what my view would interpret as Matthew’s bringing woes pronounced by Jesus in different places in Luke together to present as a single unit in his twenty-third chapter. The way he gleans the woes from Luke 11’s story of the dispute over hand washing at a Pharisee’s house, yet without retaining anything further from the original context in which the woes appeared, is illustrative of his larger approach. Matthew's basic text was Mark which he supplemented in a such a way that it is fairly easy to follow what he is doing a he goes along. And so, while both of these criticisms may be reckoned by some to be the ‘greatest weakness,’ of my view, that is not how they strike me. I leave aside for another occasion discussion of one other treatment which has been presented, which does not reflect an awareness of my particular understanding of Matthew’s compositional process, nor in fact of any of my arguments, but which nevertheless definitively claims to disprove my thesis, namely F. Gerald Downing’s “Plausibility, Probability, and Synoptic Hypotheses,” Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 93.2 (2017): 313-37. For the time being I commend to my reader the very satisfactory response Alan Garrow has provided, in his last few posts. So, in the end the question of the ‘greatest weakness,’ does come back to me. When I read my synopsis I do not find myself hitting a brick wall as I once did when trying to validate first Griesbach then Farrer. But I do encounter uncertainty as to whether two statements in the conclusion of my original article are really true. The first statement was: “Matthean Posteriority, with the single qualification that Matthew viewed Mark as his primary but Luke as a supplementary source, appears to be a simple and compelling solution to the problem of Synoptic relationships.”[4] I often find myself asking: “is it really?” Is that “single qualification” really adequate to cover all we see going on in the double tradition, in the material normally identified as Q? And my question keeps bringing me back to the original language of my statement. Yes it does “appear to.” But I would like to be able to come to a place where I could state that more definitively. Then, in my second statement I suggested that, ‘an examination of the infancy and resurrection narratives with an eye on known Matthean redactional preferences does nothing to undermine the conclusion that in these sections Matthew has been informed but not controlled by his familiarity with Luke.’[5] But again, are the words ‘does nothing to undermine’ too definitive? After all, there are significant differences that can legitimately be thought to point to Matthew and Luke’s not knowing one another’s Gospels, including, for example, the completely different genealogies. Now when comparing the Farrer Hypothesis with my solution in these sections it seems obvious to me that Matthean Posteriority makes more sense, but when comparing it with the two-source theory again I sometimes wonder. Should I have written ‘need not undermine’ instead of ‘does nothing to undermine’? Perhaps. Ultimately, my ongoing questioning in both cases stems from a desire for greater certainty than may ever be achievable given the nature of the evidence. A certain level of healthy doubt, as it were, may just go with the territory when it comes to trying to credibly sort out the question of literary interdependencies in the Synoptic Gospels." ------ [1]Paul Foster, “Is It Possible to Dispense with Q,” Novum Testamentum45.4 (2003): 336. [2]Ibid., 336, n. 98. [3]Joseph Verheyden, “A Road to Nowhere?: A Critical Look at the “Matthean Posteriority” Hypothesis and What It Means for Q,” (2010): 8-9. [4]Ronald V. Huggins, “Matthean Posteriority: A preliminary Proposal,”Novum Testamentum34:1 (1992): 22. [5]Ibid.

Ron writes: "In response to this question, it must first be asked, ‘“biggest weakness” according to whom?’ The obvious answer, of course, is according to me. But the shape given my thinking on the subject involves a great deal more than just me. It is in fact very much contingent on my belief regarding who might be right if I turn out to be wrong. And there the answer is clear. If my view, Matthean Posteriority (Luke depending on Mark and Matthew depending on Mark and Luke), is wrong, then the closest one to being right will be something like the dominant two-source theory (Matthew and Luke depending on Mark and Q, but not on one another). I use the words “something like,” because even though I am firmly convinced that the two-source theory is far superior than its other competitors (see below), I still think it is in need of correction and clarification at certain crucial points. It’s just a simple fact that holding a dominant consensus view puts one at one’s ease in such a way that it becomes easier to allow oneself the luxury of becoming less critical and of confidently repeating arguments whose force are perhaps more presumed than real. And in my view, this has been the case with the two-source theory as it is has been traditionally presented and defended. But let me turn to those “other competitors” mentioned above.

I find it incredible that anyone who really understood the explanatory force of the dominant two-source theory would abandon it in favor of either the Griesbach Hypothesis (Matthew first, Luke used Matthew, Mark used both) or the Farrer Hypothesis (Mark first, Matthew used Mark, Luke used both). Those who do abandon the two-source theory often admit that the reason they’d adopted it in the first place was that they’d been taught that it was the ‘right’ view, the one ‘most scholars’ embraced in introductory text books they’d read in the early stages of their scholarly formation or teachers they respected. Typical of this is the story of prominent Griesbach reviver William R. Farmer, who tells how at the beginning of his career he both embraced and taught Markan priority not because he understood the force of the arguments underpinning it, but because “it was an unquestioned part of an unquestioned tradition passed on to me by my teachers, whom I knew personally to be trustworthy and had good reasons to believe were professionally competent.”[1] This way of coming to a particular position on the Synoptic Problem of course applies to the embracing of other solutions as well. All of us tend to want to believe those we respect and admire. We saw this influence in action in this very blog in the past week or so as Alan Garrow and Rob MacEwen wrote of the impact of non-two-source theorists R. T. France and Harold Hoehner on their early thinking. I believe as well, that some reject the two-source hypothesis without understanding it because they are naturally endowed with a contrarian spirit which inclines them toward rejecting consensus views simply because they are consensus views, and equally inclined to reject any solution they’d been taught by what they deemed an authoritative voice. One can often recognize refutations coming from such personalities by their unshakable confidence, absolute dismissiveness, and incendiary rhetoric. They often express absolute certainty that there is nothing to commend the two-source theory at all. Perhaps no better example of this can be given than a remark made last year by the historical-Jesus denier Richard Carrier, who wrote: “Q never existed. And there is no rational reason to believe it did. Instead, it is defended with a panoply of lies and blatant violations of logic. A lot like the historicity of Jesus.”[2] In this type of two-source denier we detect a species of the character St. Augustine described who was habitually inclined to “receive what is false as if it were true, reject what is true as if it were false, and cling to what is uncertain as if it were certain.”[3] Now to be sure, the counterpart of the contrarian is the person who does the opposite, who embraces the consensus view and sticks with it no matter what, not because they understand it, but because it is the consensus view. But I am not talking about them here. The reason that abandoning the two-source theory in favor of Griesbach or Farrer makes no sense is that the former thesis is simple, elegant and has considerable explanatory power, while the latter both require an elaborate supporting superstructure consisting of a multiplicity of ad hoc arguments just to keep them afloat. They are the sort of theses my old professor Bruce Waltke once described by saying: First you decide what your thesis is, and then you spend the rest of your time inventing arguments to dismiss all the evidence that stands against it. Long story short, Griesbach and Farrer aren’t simple, nor elegant, and they lack sufficient explanatory power. I experienced this first-hand when I tried to convince myself of the validity of each of the two views in turn. The problem is well put by Richard Bauckham only a few days ago on this blog in reference to the Farrer Hypothesis: “Francis Watson in his book Gospel Writing has now made the best available attempt to explain and account for Luke’s compositional procedure. I doubt if anyone could do better, but I ended reading it with the conclusion: This is unbelievably complex. It is also completely unparalleled in the way that other ancient authors worked with their sources.” The point is that if Matthean Posteriority is ever toppled by weaknesses detected in it, it will still remain a better solution, simpler, more elegant, and with more to commend it, than the Farrer or Griesbach Hypotheses. Unlike those solutions, I believe it commends itself to those who have already grasped the inner workings of the two-source theory, understood its strengths, and yet from time to time bumped up against certain issues and blind spots in its defense and application. The result is that a move over to Matthean Posteriority feels more like taking an additional step in the same direction, rather than slamming one’s synoptic logic into reverse, backing all the way out to the main road, and heading off in an entirely different direction. Matthean Posteriority affirms many of the insights of the two-source theory which Farrer and Griesbach positively deny." Part 2 of Ron's piece will be published tomorrow. -------- [1]William Farmer, “The Case for the Two Gospel Hypothesis,” Rethinking the Synoptic Problem (ed. David Alan Black and David R. Beck (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2001), 97. [2]Richard Carrier, “Why Do We Still believe in Q,”(April 26, 2017): https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/12352. [3]Augustine, Enchiridion on Faith, Hope, and Love21. Gerald Downing has, over many years, built a reputation for an understanding of ancient compositional practices. He has, very effectively, used this expertise to demonstrate that the actions required of Luke and Mark, under the Farrer Hypothesis (FH) and Two Gospels Hypothesis (2GH) respectively, have no precedent or equivalent in ancient practice and that, furthermore, the physical difficulty of the innovations required would have been prohibitive.

In ‘Plausibilty, Probability, and Synoptic Hypotheses’ ETL (2017) 313-337, Downing brings his expertise to bear on the proposal that Matthew used Luke (and Mark). He uses ‘Mt3rd’ to designate this type of hypothesis. Critical to Downing’s approach is an appeal to statements by Tacitus, "Where the authorities are unanimous, I shall follow them" and Arrian, "Whenever Ptolemy son of Lagus and Aristobulous son of Aristobolous have both given the same accounts ... it is my practice to record what they say as completely true" (p. 322). There are two ways to interpret these statements. On the one hand, it may be that Arrian and Tacitus were expressing the view that, when two sources recalled the same event (albeit in different ways) they regard the event as highly likely to have actually taken place. On the other hand, it is possible that what they meant was that, wherever their sources used an identical string of words to describe an element of a particular incident, their practice was to use exactly the same words in their third account. For Downing’s attack on Mt3rd to be effective, it is important that they meant the latter – and that their practice was one Matthew felt compelled also to observe. One way to check what Arrian and Tacitus meant by their statements would be to consult their sources and see how they actually behave. Unfortunately, there are very few instances where the full triangle of sources is still available for us to consult. There is, however, a different way we can approach this puzzle. One piece of information we do have to hand is how ancient authors generally treated their single sources; they tended to render these sources in their own words. This creates an initial difficulty for Downing’s interpretation of Arrian’s and Tacitus’ statements inasmuch as it reduces the likelihood that the sources to which these ancient authors had access included extensive verbatim similarities in the first place. A second relevant piece of information is that, for practical and physical reasons, ancient authors would have found it exceptionally difficult to keep their eye on two sources at the same time. In fact, this reality still persists today inasmuch as human beings still find it hard to read two texts simultaneously. This means that any ancient author seeking to copy strings of letters precisely shared by two sources would be required to devote a great deal of effort to identifying where these duplications actually occurred – so as to be sure never to miss these elements of double witness. This is the point I sought to make in yesterday’s post. And, their reward for success in this exceptionally difficult task would be the security of knowing that they’d got the words exactly right … except that ‘getting the words exactly right’ seems otherwise to be remarkably low on the agenda of these writers; their preference was to paraphrase rather than copy verbatim. It may be preferable to suspect, therefore, that what Tacitus and Arrian meant was not that they felt bound to identify and copy every string of agreement in parallel sources, but that when two sources recalled the same incident they treated that incident as likely to have taken place. And, when it came to their own presentation of that incident it seems likely that they would have followed one of those two sources, while perhaps also bringing in supplementary details from the other, while perhaps also presenting the entire episode in their own words. Nevertheless, Downing states: ‘In the light of current conventional preference for common witness, [Matthew failing to copy doubly attested strings of letters found in Mark and Luke] would have been absurd’ (p. 335). According to Downing, Matthew would have had his hands tied. He would have had a duty to seek out exactly agreeing phrases in Mark and Luke, no matter how incidental to the narrative, and a duty to find a way of faithfully incorporating them into his account no matter the effect on his narrative. I suggest, by contrast, that Matthew would always have retained editorial freedom and would have tended to work from one text at time, while also drawing in additional valuable information from his supplementary sources. Downing’s overall contention is that Mt3rd is ‘impossible’ and that the 2DH faces some difficulties which, with a little ingenuity, may be overcome. I suggest, however, that he overestimates the scale of any problem with Mt3rd to about the degree that he underestimates the multiple difficulties affecting the 2DH. Tomorrow Ron Huggins reflects on what he sees as the greatest weakness of his Matthean Posteriority Hypothesis. Gerald Downing sets his readers challenge on pp. 330-1. He invites us to find some particular extended strings of letters that are closely mimicked in both texts, 'so as to know what Mt3rd is going to avoid'. He uses continuous majuscule text to more closely mimic the mass of letters that would have confronted Matthew if he were working from manuscripts of Mark and Luke. Even then, however, the true difficulty of the task is only hinted at because, of course, it is highly unlikely that the texts in Matthew's possession would have been so neatly and regularly scribed, and Matthew would not have been able to set them beside one another so closely. If you would like to try playing this game yourself, Downing invites you to look for: ΕΛΑΙΩΝΑΠΕΣΤΕΙΛΕΝΔΥΟΤΩΝΜΑΘΗΤΩΝΛΕΓΩΝΥΠΑΓΕΤΕΕΙΣΤΗΝΚΑΤΕΝΑΝΤΙΚΩΜΗΝΕΝΗΙΕΙΣΠΟΡΕΥΟΜΕΝΟΙ ΕΥΡΗΣΕΤΕΠΩΛΟΝΔΕΔΕΜΕΝΟΝΕΦΟΝΟΥΔΕΙΣΟΥΠΩΑΝΘΡΩΠΩΝΕΚΑΘΙΣΕΝ ΟΚΥΡΙΟΣΑΥΤΟΥΧΡΕΙΑΝΕΧΕΙ ΚΑΙΕΙΣΕΛΘΩΝΕΙΣΤΟΙΕΡΟΝΗΡΞΑΤΟΕΚΒΑΛΛΕΙΝΤΟΥΣΠΩΛΟΥΝΤΑΣ (the last of these is highlighted for you)

Downing's point is that it is truly remarkable that Matthew succeeds in 'assiduously avoiding' (p. 336) almost every one of the strings of 30+ letters shared virtually identically by Mark and Luke. [NB, by 'avoid' Downing means 'fail to copy verbatim' rather than 'omit altogether' cf. yesterday's post]. He suggests that 'had Mt3rd actually wanted to miss dual UCVSTs, then with both the texts before him, he could have physically done it, painstakingly. I must allow that it would have been physically possible, even if still quite difficult, time consuming. But why?' (p. 335). This is a fair point. It would have taken extraordinary labour to pick out these strings of agreement so as specifically to 'avoid' them. The only problem is that, just three paragraphs earlier, Downing states that: 'With that keen attention, mainly to Mark, but constantly aware of Luke, [Mt3rd] could hardly have failed to notice this common matter. Indeed, as argued, we would expect him to look for it, and value it. But he does not' (p. 334). Downing can't have it both ways. This common material is difficult to spot whether one wishes to include it or exclude it. Indeed, I struggle to imagine how such inclusion or exclusion could have been achieved without the use of a highlighter pen – or its ancient equivalent. What I mean is that, before actually starting work on his Gospel, Matthew would be required to work his way through Mark and Luke in parallel ‘highlighting’ all those passages where 30+ letters agree exactly. Without preparatory work of this kind how could Matthew have been alert (when working from one text or the other) to the presence a double-attested string of letters, so as to be sure to include it (or exclude it)? Furthermore, if Matthew did find some means remaining alert to this phenomenon, is it realistic to imagine that he would have surrendered all editorial autonomy at these points – no matter the consequences for the theology, economy, or coherence of his own creation? Downing concludes that for Matthew, 'regularly to exclude extensive common witness while using the other two is totally implausible, quite impossible to imagine coherently' (p. 336). However, if by 'exclude' we actually mean ‘express editorial freedom in relation to’, the imagination is barely taxed at all. All that is required is to imagine that Matthew saw himself as having the freedom to edit his sources as he saw fit, especially where elements of those sources were non-critical. And, as the coherence of the text of Matthew’s Gospel demonstrates, the exact preservation of these particular (very difficult to identify) word-strings is indeed non-critical. As an alternative to Downing’s model I suggest that Matthew was a conflator who sought to supplement what he found in Mark with the additional material he found in Luke (and elsewhere) – while also serving his own theological agenda (cf. Huggins, 1992). If this supposition is not too far-fetched, we would expect Matthew to follow Mark (editing along the way) while also sometimes switching to Luke (also editing as necessary). Under this arrangement, (and contrary to Downing’s firm expectation), the elements of Luke that would have been of least interest to Matthew would have been those where Luke was exactly similar to Mark. Conversely, the elements of Luke that would have been most interesting to Matthew would have been those places where Luke included further, valuable, supplementary material. Given that this imaginative scenario explains the data while also placing Matthew third, it really is not true to claim that Mt3rd is: ‘totally implausible, quite impossible to imagine coherently' (p. 336). Tomorrow I conclude this set of responses by noting the larger implication revealed by Downing's argument. In yesterday’s post I tried to explain the basis for Gerald Downing’s claim that Matt3rd is ‘impossible’. Downing’s contention, in essence, is that: if Matthew knew Mark and Luke, then, when Mark and Luke agree verbatim for 30+ letters, Matthew ought to mimic this double attestation exactly. Here is his point in his own words: Mt3rd appears to have refused to include such further common matter [which Downing calls ‘UCVSTs’ (Unconventional Verbatim Shared Texts) by which he means passages that are not: words addressed to Jesus, words of Jesus, challenges to Jesus, words of the Baptist, or words of God] as it stands, or, on occasion, even refused to paraphrase it, all alongside often accepting extensive single witness verbatim. … To repeat, apart from one thirty-letter instance, no full-length triple UCVSTs appears in Matt, despite the numerous double UCVSTs in Mark-with-Luke waiting to be accepted. This puzzles me, and perhaps will or should in due course puzzle the reader. (p. 320) As I mentioned in yesterday’s post, it is important to understand precisely what Downing means by ‘refuse’ or ‘avoid’ or, ‘assiduously avoid’. What he does not mean is ‘completely omit’, what he does mean is ‘fail to copy exactly’. To provide a more precise understanding of this point, here are the first ten instances (out of a total of forty-two) where Downing spots strings of 30+ letters in Mark and Luke which, he claims, Mt3rd assiduously avoids (with the exception of Example 6, where Downing detects a single example of Mt3rd behaving as he would expect).

Example 1. Mark 1.4//Luke 3.3: κηρύσσω βάπτισμα μετανοίας εἰς ἄφεσιν ἁμαρτιῶν [preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins]. Matthew: omits entirely. Example 2 Mark 1.7//Luke 3.16: ἔρχεται [δὲ] ὁἰσχυρότερος μου [ὀπίσω μου] οὗοὐκ εἰμι ἱκανος [κύψας] λῦσαι τὸν ἱμάντα τῶν ὑποδημάτων αὐτοῦ [after me comes he who is mightier than I, the thong of whose sandals I am not worthy to stoop down and untie] (Mark 1.7//Luke 3.16). Matthew 3.11: ὁδὲὀπίσω μουἐρχόμενος ἰσχυρότερος μου ἐστιν οὗοὐκ εἰμι ἱκανος τὰὑποδημάτων βαστάσαι [but he who is coming after me is mightier than I, whose sandals I am not worthy to carry] Example 3 Mark 1.13//Luke 4.1: ἐν τῇἐρήμῳ[τεσσεράκοντα ἡμερας reverse order in Luke] πειραζόμενος ὑπο τοῦ... [in the wilderness forty days tempted by ...] Matthew 4.1-2: εἰς τὴν ἔρημον ὑπὸτοῦπνεύματος πειρασθῆναι ὑπὸδιαβόλου και νηστεύσας ἡμέρας τεσσεράκοντα [into the wilderness by the Spirit to be tempted by the devil. And he fasted forty days]. Example 4 and 5 Mark 1.23-28//Luke 4.33-37 ‘The Healing of the Demoniac in the Synagogue’ includes duplicate strings, one 114 characters long and the other 35. Matthew omits the entire episode. Example 6 (not numbered by Downing) Mark 1.22//Luke 4.32: καὶ ἐξεπλήσσοντο ἐπὶτῇδιδαχῇαὐτοῦ [And they were astonished at his teaching] Matthew 7.28:ἐξεπλήσσοντο [οἱ ὄχλοι] ἐπὶτῇδιδαχῇαὐτοῦ [the crowds were astonished at his teaching] Example 7 (Downing 6) Mark 1.4b//Luke 5.14a: τῷἱερεῖκαὶπροσένεγκε περι τοῦκαθαρισμοῦσου [… to the priest and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded you] Matthew 8.4a: τῷἱερεῖκαὶπροσένεγκον [ … to the priest and offer (the gift that Moses commanded)] Example 8 (Downing 7) Mark 4.41//Luke 8.25: πρὸς ἀλλήλους τίς ἄρα οὗτός ἐστιν ὅτι και [… to one another: “Who then is this …]. Matthew 8.27: ποταπός ἐστιν οὗτος ὅτι και [“What sort of man is this …]. Example 9 (Downing 8) Mark 5.7-8//Luke 8.28-29: τί ἐμοὶκαὶσοί Ἰησοῦυἱε τοῦθεοῦτοῦὑψίστου; [‘What you you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God?’]. Matthew 8.29: τί ἡμῖν καὶσοί υἱε τοῦθεοῦ; [‘What do you have to do with us, O Son of God?’]. Example 10 (Downing 9) Mark 5.13/Luke 8.33: εἰσῆλθον εἰς τοὺς χοίρους καὶὥρμησεν ἡἀγέλη κατὰτοῦκρημνοῦεἰς τὴν... [entered the swine and the herd rushed down the steep bank] (into the sea/lake). Matthew 8.32: ἀπῆλθον εἰς τοὺς χοίρους καὶἰδοὺὥρμησεν πασα ἡἀγέλη κατὰτοῦκρημνοῦεἰς τὴν θάλασσαν [and went into the swine and behold the whole herd rushed down the steep bank into the sea]. In the case of the first instance Downing generously notes that Matthew might possibly have chosen to omit these words so as to allow the privilege of forgiveness of sins to Jesus alone. However, he goes on to protest: '[A]re we going to have to find a lot of such ad hoc explanations for over forty more Mark/Luke common texts "happening" to displease this redactor?' (p. 322). If, however, Matthew’s redaction of these passages in Mark (under the 2DH) makes sense, then why should Matthew’s redaction of these passages make less sense simply because the passages in question happen to appear in both Mark and Luke? If Matthew had a logical reason to make a change in one case, then exactly the same logic would apply in the other. Tomorrow I will ask what would satisfy Downing that Matthew had used Luke and Mark – while also asking if this standard could ever, in reality, be achieved. |

AuthorAlan Garrow is Vicar of St Peter's Harrogate and a member of SCIBS at the University of Sheffield. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed