| Alan Garrow Didache |

the problem page

|

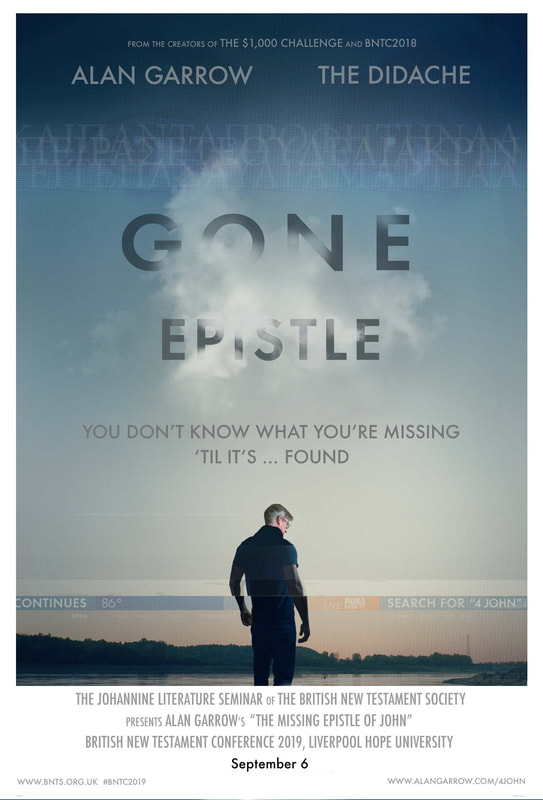

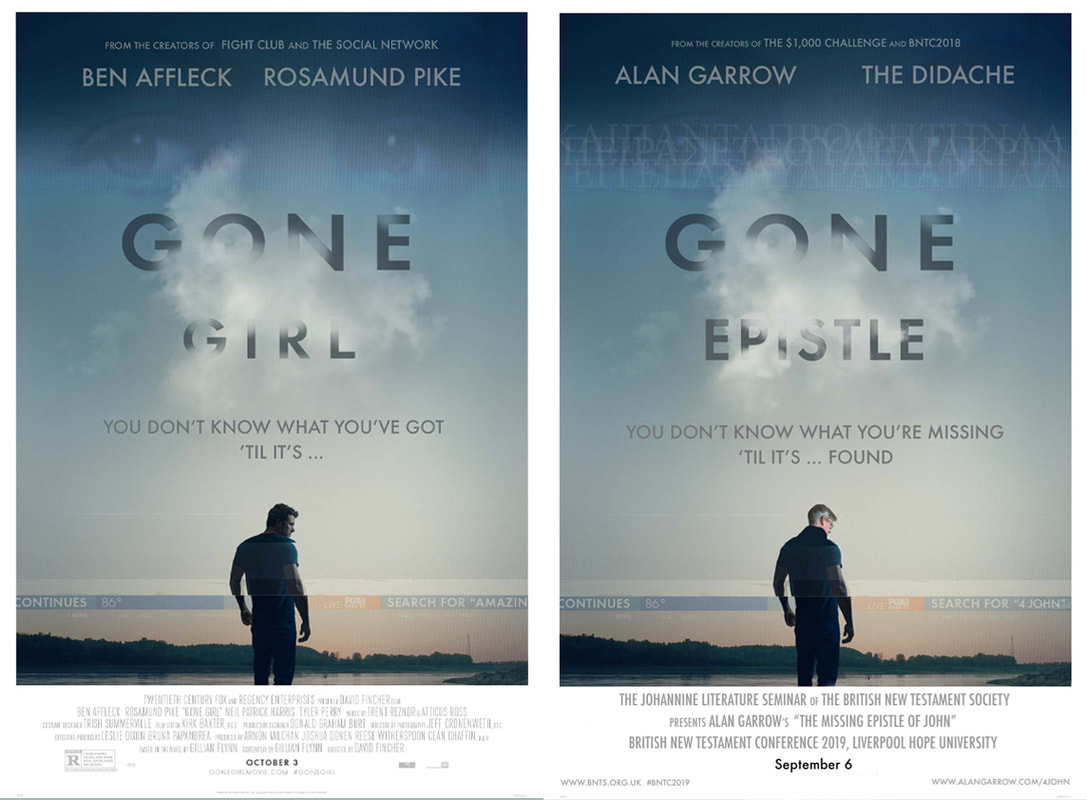

This poster serves as an abstract for a paper due to be delivered at this year's British New Testament Conference. The text version is available here. If you enjoy spot the difference:

0 Comments

The Synoptic Problem, Brexit and why people sometimes read the same data to opposite effect14/6/2019 In a recent Facebook exchange a well-informed conversation partner made an observation along the lines: isn't it remarkable that supporters of the Farrer Hypothesis, Two Document Hypothesis and Matthew Conflator Hypothesis (FH, 2DH and MCH) can all look at the same data and confidently read it as pointing to their favoured solution to the Synoptic Problem - and not their opponents'? I'd like to try to explain how this happens using the illustration of Brexit.

The case for Brexit is clear. A country wishing to have control over its own destiny cannot afford to be governed by other people in another country, etc. - it's obvious! The case for the UK remaining in the European Union is clear. Our economic systems are inextricably linked with that of our European partners. To rip away from those systems would be economically disastrous, etc. - it's obvious! Depending on whether you find the political or the economic argument more compelling, you choose your side in the debate. Having made that decision this then provides the lens through which all further data is viewed. Those who disagree with you seem increasingly blind and obtuse. 'Why can you not see the negative effects of your position!' - we scream as the divide gets wider. At the same time, the weaknesses of our own position go through a process of minimisation; they pale into insignificance beside the monstrous problems with the other side of the argument. Something similar has happened, I think, in the debate between supporters of the 2DH and the FH. The former are usually open about the fact that their hypothesis doesn't perfectly resolve every bit of data - but they stick with it because they are so convinced that Luke's use of Mathew is impossible. Farrer supporters, on the other hand, are frustrated by the fact that their opponents continue to wave away evidence that, in any other context, would be taken as a clear indication of direct copying between Matthew and Luke. So long as we are forced to choose between binary options, 2DH or FH, Leave or Remain, there is a tendency to focus on one piece of data, form a position on that basis, and then read all the other data through that lens - constantly highlighting the difficulties of the opposite view while seeking to minimise or explain away the problems in our own back yard. In the case of Brexit, unfortunately, we can't wind back the clock. If we could, then we might be able to take different decisions to avoid the mess we're in now. In the case of the Synoptic Problem, however, we do have that luxury. In my article "Streeter's 'Other' Synoptic Solution: The Matthew Conflated Hypothesis" I wind back to some false decisions made by BH Streeter and scholars of his generation - which have been repeated (and thereby consolidated) ever since. Streeter made two critical logical errors. 1) He assumed that arguments against Luke's use of Matthew amounted to arguments against Matthew's use of Luke. 2) He assumed that evidence that Matthew and Luke shared a source or sources (other than Mark) amounted to evidence that Matthew and Luke had no direct contact with one another. Both these assumptions are false. We will never escape the Synoptic Problem's binary bind until we reckon with these simple, unavoidable errors. When the errors of the Streeter generation are acknowledged, the log-jam eases. A third option, which preserves all the benefits of the 2DH and also the benefits of the FH, comes into view. It is no longer necessary to choose an option that is 'not as bad' as the binary alternative, it is possible to choose an option that resolves all the data while allowing every player, Mark, Luke and Matthew, to behave in a consistent manner. Mark wrote first, Luke incorporated Mark in blocks, Matthew used Mark as a spine and conflated in related material from Luke and other sources (some of which were also known and used by Luke) to create his thematically arranged gospel. That, then, is my explanation of why three scholars can look at the same data with such variable results. The first two are caught in a binary contest where both sides have significant strengths as well as significant weaknesses. When, however, the basis of that binary set-up is challenged, a third way of looking at things can come into view. In scholarship we have the freedom to retrace our steps and untangle the mistakes of our predecessors. Most unfortunately, we don't have the same privilege in politics. |

AuthorAlan Garrow is Vicar of St Peter's Harrogate and a member of SCIBS at the University of Sheffield. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed